“A Conversation with Ariel Schlesinger”

Rob Franciosi

“April is the cruelest month,” T.S. Eliot famously wrote, a line that came to me on a cold and rainy Friday when I walked the site where Ariel Schlesinger’s Ways to Say Goodbye is to be situated. The achingly slow Michigan spring presented a landscape that was muddy and colorless, which seemed appropriate to the disaster that Ways to Say Goodbye would commemorate.

These morose thoughts, however, soon yielded to others fueled by the still-lingering warmth of my encounter with the artist. Clad in a bright crimson coat—far too thin, I thought, for tromping the site at Meijer Gardens, I thought—Ariel Schlesinger at first glance seemed the typical New York artist. He had even just moved to Brooklyn, to live among all the other artists and writers, which I told him seemed like requiring new college students to live on campus. These surface impressions soon gave way, revealing a man who was both engaging and gentle, interested in talking about his work, yes, but not in a way that sucks all the oxygen out of the room.

I so enjoyed our conversation that it seemed worthwhile to continue it in another form. We started out doing a back-and-forth e-mail exchange, but finally settled on a Zoom discussion. What follows is an amalgamation of the two exchanges and, I hope, an interesting prelude to the upcoming dedication of Ways to Say Goodbye on the last day of this month.

Rob: Your work for the Meijer Gardens of course evokes the trees that are represented at the entrance to the Frankfurt Jewish Museum. Why trees? And, more particularly, why trees without leaves?

Ariel: Trees are people, and people are trees. We all live in a forest and socialize, it’s part of our nature. It was only obvious to me that a natural element like a tree will be a center that draws people together and starts a discussion around our past and future, together.

The reason not to sculpt the leaves is a choice both visual and practical, keeping the overall elements in the object as minimal as possible.

Rob: So, to pick up on your idea of a tree as a way of drawing people together to start a conversation, what kinds of discussion do you envision Ways to Say Goodbye fostering for those who see it at the gardens?

Ariel: I see a discussion as open-ended, a start of a journey really. I can say something about how it stands straight and tall but holds in its hands and fingers sharp shattered glass, memories and ideas that seem to reflect pain on it. Another person can respond with their interpretation. I can’t control what they see in it. I think that’s the beauty of it. But I might learn something from them and maybe see it as well. We might even change each other’s perspective and hopefully learn something from the other. I think that’s the great power of looking and hearing.

Ariel Schlesinger with JFGR Campaign Director, Linda Pestka

Rob: The inclusion of glass shards in the branches of Ways to Say Goodbye will likely stimulate much conversation. Just as your joining of two trees outside the Frankfurt Jewish Museum was a provocative gesture, the entangling of glass in the Meijer Gardens tree seems to me equally compelling, particularly in a lush outdoor setting.

Ariel: That’s very much a sculptural kind of decision. I always approach my work from two directions: one is the conceptual, but the other is very much about the material. I put as much importance into each of them. I’m not somebody whose ideas overcome the form, because I also very much enjoy experiencing art through the materials, through the human, physical connection that it makes. A lot of times I feel that one can say the material overtakes the concept; but sometimes those two worlds come together and they actually help each other and make the experience of the sculpture stronger and bigger.

I feel that happens with the combination of the glass and the tree. The tree is made out of aluminum, and therefore nothing is actually alive or flexible or dynamic about it, other than the shape. And since it took almost the exact shape of the fig tree, with the surface and shape, maybe that’s when the movement happens. It’s so similar to a real tree that one almost loses the recognition that it’s a dead object. The glass, then, the way it is trapped in the branches, also brings questions: what came first, was it in the tree from the start? or was it glass that fell into the tree? Once you see this tree up close, you will find that the joints between the glass and the aluminum cast are perfectly made. It almost feels as if the glass is cut into the branches. Or that over the years the tree grew around it, the way trees surround obstacles, such as a fence.

Rob: We have a tree in our yard which has grown around a metal post. I’ve thought about trying to pull it out, but realize that I can’t. The two have become one object.

Ariel: That’s the reason, maybe, why this piece makes me think about memories and about experiences, and about catastrophes or even intentionally inflicted harm the tree may have felt in the past. And as we discussed earlier, those human pasts. That’s why I think this sculpture can function as a memorial very well, because it’s a tree that is there, it’s standing, but it doesn’t try to hide. It tries to live together with the catastrophe that it went through or the problem that it encountered. Even though it’s very intimidating, because the glass is suspended in a very fragile way over our heads, it can also be optimistic because the tree stands there with a lot of pride.

Rob: I think it’s really fascinating what you’re doing, especially the ambiguity of the glass, and reminds me of the so-called survivor trees at the memorial sites in Oklahoma City and at the World Trade Center. In both instances single trees survived the catastrophe, severely damaged, yes, but still alive–and now still blooming, symbolizing a measure of human endurance in the face of disaster.

Trees also figure prominently in certain Holocaust memorials, in which a lost community is represented by one that has been cut down. I have also seen photographs of of trees growing through ruins of synagogues in Eastern Europe, images which temper the optimism of growth with an abject sense of loss and abandonment. And I have already heard some comments regarding the glass in Ways to Say Goodbye as perhaps representing Kristallnacht.

Ariel: Yes, working with glass actually started with me, interestingly enough, through a series of works that are based on Kristallnacht. I think that’s why I arrived at using glass a few years earlier before making this particular sculpture.

I was working a lot with shattered windows, breaking them and then gluing them together, and then photographing them. This was a response to art history in a way, being about the object and then the representation of the object. The way I worked was that after breaking the glass, putting it back together, and then installing it back in the window, I photographed the window—but the focus was not on what the window showed, inside or outside, but on the glass. Then, when I printed the photograph, I framed it using the broken glass. Finally, you have the object and you are viewing the documentation of the object through that object. This was also a reference to the Charlie Chaplin movie, The Kid, in which he teams up with an orphan kid runs who around the neighborhood throwing rocks at windows. Chaplin then shows up to repair the glass That was another reference to the gallery or art world, where we are selling these broken windows. So, I was breaking the windows of the gallery space, reframing them, and then selling them.

But through that fascination with the broken, shattered glass, I actually did a series on Kristallnacht. Very similar, as I broke a mirror and then re-glued and reframed it, but I used found photos from Kristallnacht. In that series I introduced another element, which was the mirror. In some of those shattered pieces you could actually see the reflection of yourself. So, it was not any more the object and the representation of the object, but more involving the viewer in the work, to become part of the work. You see your reflection, as well as the mess of the Kristallnacht in a very blurry, black and white snap shot. By working with shattered glass, I discovered how to work with it—and that’s how I could use it in the tree.

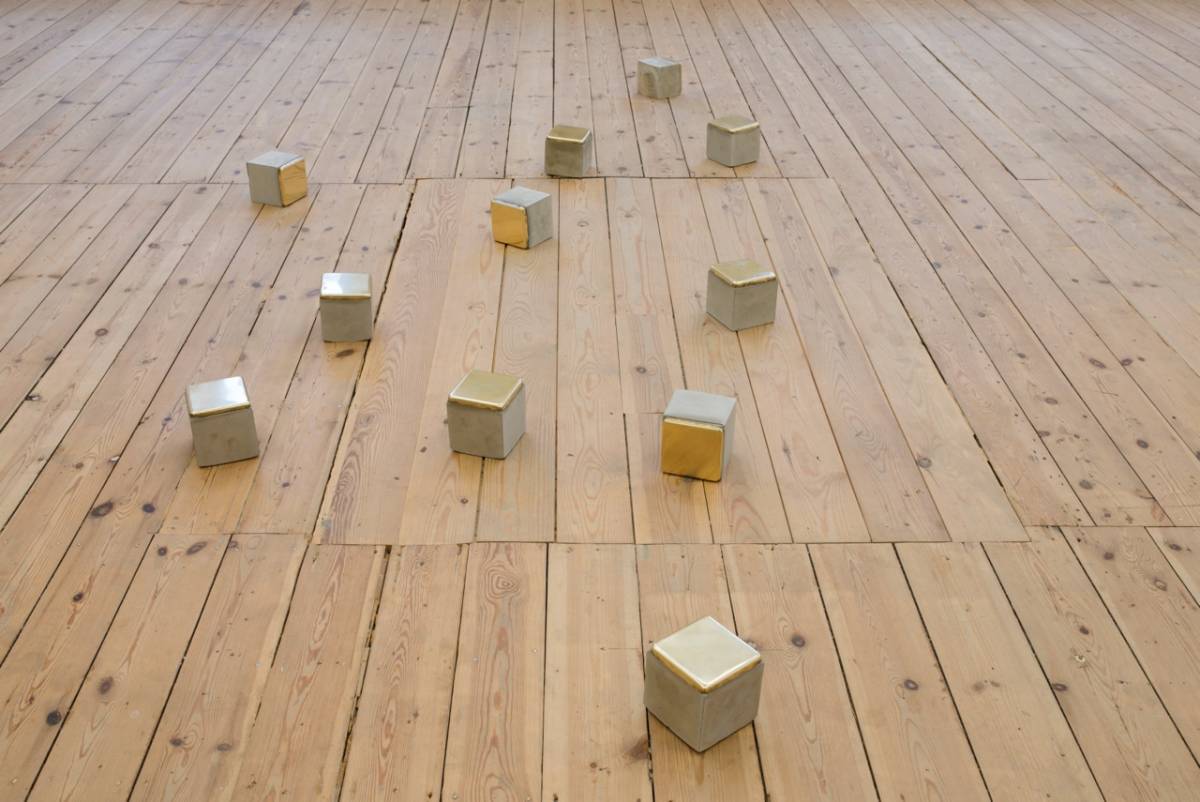

Rob: Because I have a particular interest in the stolperstein project in Europe and will be in Berlin this fall for an installation, I was intrigued to discover your work with the form. The whole point of a stolperstein is to inscribe a person’s name and tie it to a specific place, yet you do something quite different, using blank stones and moving them to various sites, including an art museum in Münster, Germany. What drew you to those figures?

Ariel: It started because I had been to Berlin and I’m Jewish, so my attention was naturally drawn to that memorial. And I immediately liked it very much, because I found it in a way very nonintrusive, but at the same time very present. I like things in the street because as an artist I was always collecting things in the street, so I was very aware of the public environment. I also liked that it was kind of an empty space memorial, comparable to the one dedicated to the burned books in Berlin, a sort of anti-space. Since that was in my mind, after a few years I began to become very curious about what was underneath in the ground. I did some more research and discovered that it is actually a cobblestone, a cube. I found that cube to be beautiful in itself, at least the combination of the material, and it led me to the idea of reproducing that block. What I wanted to show was that this can happen anywhere, this can happen to anybody, especially in thinking about living in Europe, thinking about migration and the forced displacement of people. I think it’s also about being Israeli and thinking about what we as Israelis do to Palestinians.

Rob: The stolperstein project is placed centered, marking where a person once lived, but once you pull those markers out, in essence putting them in the open air, then all that you mention is up for discussion.

Ariel: Basically, I wanted to open it up to a memorial, to a work of art, that can move, like any kind of people, which also suggests that it can happen anywhere, being forced on people everywhere. I remember that it was during the big Syrian refugee crisis, and even before that the arrival in Europe of many migrants from Africa. I don’t remember what exactly was on the news at that time, but I do remember that that was my suggestion. That’s why the piece was kind of free, the arrangement more or less random. You could place these blocks anywhere, there was no code or instruction that I asked them to be placed in a certain way. That’s what you saw in an exhibition in Münster.

Rob: Your piece outside the museum in Frankfurt is located in a city with a rather small Jewish community, less than 1% of the city’s population, much like Grand Rapids. The vast majority of people who visit Meijer Gardens and see your piece will not be Jewish. What do you hope they will take away from the encounter?

Ariel: I hope that they will see a work of art by the grandchild of a survivor and perhaps through accompanying text will see how that person experienced and translated the stories of his family and of his community. Of how he created his art and lived his life with those memories and with those stories. For me it’s a very personal process and maybe they can read it through me. I cannot teach them or say “this is how it happened,” because I was not there, and they weren’t, but I hope that the sculpture will open a sort of dialogue, to enrich their knowledge and their opinions.

Rob: The title Ways to Say Goodbye raises all sorts of questions about the idea of saying goodbye to the past, especially for the grandchild of Holocaust survivors. Mourning is not about being focused strictly on the past, after all, but on being able to move beyond it; not to forget, but not to be trapped by it. In that respect, a tree, though wounded in the past, promises growth in the future.

Ariel: Just like the stolpersteine, we are offering an idea, a way of thought. I think it is much more effective to offer it rather than to point it out. I feel there are so many references within the piece: what trees represent in Judaism, the shattered glass of Kristallnacht, those memories, the title, who I am as an artist, the story of the Pestka family who sponsored the work. There are so many elements that I hope will create a space for discussion.

Rob: The Meijer Gardens site also brings the advantage of the four seasons. I’m especially looking forward to encountering Ways to Say Goodbye in the middle of the winter, when it’s windswept and there’s no one else around. But also seeing it in spring. And unlike your piece in the urban setting of the Frankfurt Museum, the space in the gardens will be natural, almost pastoral.

Ariel: Yes, we tried to define that space using a concrete path, but the hilltop still encloses the piece, allowing it to blend in. While the plaza provides a place to sit down, to hang out, so you are close to it, under it, you are also away from it at the same time. I think it’s true that the tree will live there among nature more than if it had been situated on cement, as in Frankfurt.

Rob: I find that a much more positive gesture then the massive memorial in the center of Berlin, which is both impressive yet excessive.

Ariel: Yes, that sense of order. I like that memorial, but it’s true that it offers less dialogue, I think, apart from being controversial, how it happened to be, as there were a lot of objections to it. I find the one where they burned the books much more interesting, because it is as if it is not there.

Rob: We’re speaking now in early May and Ways to Say Goodbye will be dedicated at the end of June. What still needs to happen?

Ariel: I will soon be there for the construction. The piece weighs two to three tons, but that’s because of the inside structure of the stainless steel, a very massive pipe. The aluminum itself is very light. And the glass weighs a lot as well. Structurally, aluminum cannot bear much weight, so they have to use proper steel piping for which they know the strength exactly, because the aluminum enclosure has no structural properties.

Rob: Are sculptors also engineers?

Ariel: These days an artist just out-sources that work. There are very good fabricators, but of course you need to know what you ask of them and how to ask it. Sometimes what I’m interested in is maybe extending the possibilities, stretching what’s possible. A lot of times it’s those companies that take drawings from artists to build the piece. Today the life of the artist can be more one of directing, but I am really interested in the construction of things. For a lot of my more complicated works I start by doing prototypes to try to see if they work, and then maybe outsourcing them to a fabricator. In this case we did a lot of testing with a combination of aluminum and glass, so that it felt right with the material and how it is held together.

Rob: The sculptor is more the leader of a creative group than an engineer or fabricator.

Ariel: Yes, the artist is a conductor.