“The memorial has important significance to my family because our father was a survivor. The numbers 73847 are numbers that we will never forget. They were tattooed to my father’s forearm, as though he were an animal, as identification for his potential death. It is our duty to educate, respect and honor the victims and their families of the unthinkable acts against life and morality. The Holocaust did happen. Holocaust deniers are reporting false and harmful information. Anti-semitism and other hate crimes are on the rise. The Meijer Garden Memorial will allow hundreds of thousands of people to become educated and aware of the atrocities against humanity. May we never forget.”

– Linda Pestka, daughter of Henry Pestka, survivor of the Holocaust

The Holocaust was the systematic, state-sponsored persecution and murder of six million Jews by the Nazi regime and its allies and collaborators. Holocaust is a word of Greek origin meaning “sacrifice by fire.” The Nazis, who came to power in Germany in January 1933, believed that Germans were “racially superior” and that the Jews, deemed “inferior,” were an alien threat to the so-called German racial community.

During the Nazi era, German authorities also targeted other groups because of their perceived racial and biological inferiority: Roma (Gypsies), people with disabilities, some of the Slavic peoples (Poles, Russians, and others), Soviet prisoners of war, and Black people. Other groups were persecuted on political, ideological, and behavioral grounds, among them Communists, Socialists, Jehovah’s Witnesses, and homosexuals.

In 1933, the Jewish population of Europe stood at over nine million. Most European Jews lived in countries that Nazi Germany would occupy or influence during World War II. By the end of the war in 1945, the Germans and their allies and collaborators killed nearly two out of every three European Jews as part of the “Final Solution.”

The Nazis considered Jews to be the inferior race that posed the deadliest menace to the German Volk. Soon after they came to power, the Nazis adopted measures to exclude Jews from German economic, social and cultural life and to pressure them to emigrate. World War II provided Nazi officials with the opportunity to pursue a comprehensive, “final solution to the Jewish question”: the murder of all the Jews in Europe.

While Jews were the priority target of Nazi racism, other groups within Germany were persecuted for racial reasons, including Roma View This Term in the Glossary (then commonly called “Gypsies”), Afro-Germans, and people with mental or physical disabilities. By the end of the war, the Germans and their Axis partners murdered between 250,000 and 500,000 Roma. And between 1939 and 1945, they murdered at least 250,000 mentally or physically disabled patients, mainly German and living in institutions, in the so-called Euthanasia Program.

As Nazi tyranny spread across Europe, the Germans and their collaborators persecuted and murdered millions of other people seen as biologically inferior or dangerous. Approximately 3.3 million Soviet prisoners of war were murdered or died of starvation, disease, neglect, or brutal treatment. The Germans shot tens of thousands of non-Jewish members of the Polish intelligentsia, murdered the inhabitants of hundreds of villages in “pacification” raids in Poland and the Soviet Union, and deported millions of Polish and Soviet civilians to perform forced labor under conditions that caused many to die.

Photos of Jews in Poland getting kicked out of their synagogue.

From the earliest years of the Nazi regime, German authorities persecuted homosexuals and other Germans whose behavior did not conform to prescribed social norms (such as beggars, alcoholics, and prostitutes), incarcerating tens of thousands of them in prisons and concentration camps. German police officials similarly persecuted tens of thousands of Germans viewed as political opponents (including Communists, Socialists, Freemasons, and trade unionists) and religious dissidents (such as Jehovah’s Witnesses). Many of these individuals died as a result of maltreatment and murder.

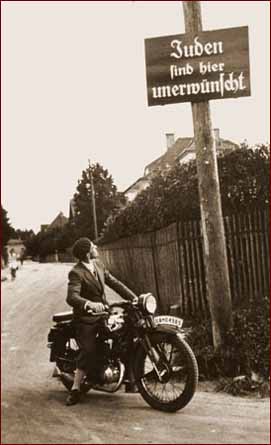

Sign in Poland: “Jews not Welcome Here”

Implementation of the “Final Solution”

World War II provided Nazi officials the opportunity to adopt more radical measures against the Jews under the pretext that they posed a threat to Germany. After occupying Poland, German authorities confined the Jewish population to ghettos, to which they also later deported thousands of Jews from the Third Reich. Hundreds of thousands of Jews died from the horrendous conditions in the ghettos in German-occupied Poland and other parts of Eastern Europe.

Following the German invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941, SS and police units perpetrated mass shootings of Jews and Roma, View This Term in the Glossary as well as Soviet Communist Party and state officials in eastern Europe. The German units involved in these massacres included Einsatzgruppen, Order Police battalions, and Waffen-SS units. As they moved through eastern Europe, these units relied on logistical support from the German military (the Wehrmacht). In addition to shootings, these units also used specially designed mobile gas vans as a means of killing. Mass shootings of Jews in eastern Europe continued throughout the war. Of the approximately 6 million Jews who died in the Holocaust, at least 1.5 million and possibly more than 2 million died in mass shootings or gas vans in Soviet territory.

In late 1941, Nazi officials opted to employ an additional method to kill Jews, one originally developed for the “Euthanasia” Program: stationary gas chambers. Between 1941 and 1944, Nazi Germany and its allies deported Jews from areas under their control to killing centers. These killing centers, often called extermination camps in English, were located in German-occupied Poland. Poison gas was the primary means of murder at these camps. Nearly 2.7 million Jews were murdered at the five killing centers: Belzec, Chelmno, Sobibor, Treblinka, and Auschwitz-Birkenau.

At the Wannsee Conference in Berlin in January 1942, the SS (the elite guard of the Nazi state) and representatives of German government ministries estimated that the “Final Solution,” the Nazi plan to kill the Jews of Europe, would involve 11 million European Jews, including those from non-occupied countries such as Ireland, Sweden, Turkey, and Great Britain.

Jews from Germany and German-occupied Europe were deported by rail to the killing centers in occupied Poland, where they were killed. The Germans attempted to disguise their intentions, referring to deportations as “resettlement to the east.” The victims were told they were to be taken to labor camps, but in reality, from 1942 onward, deportation for most Jews meant transit to killing centers and then death.

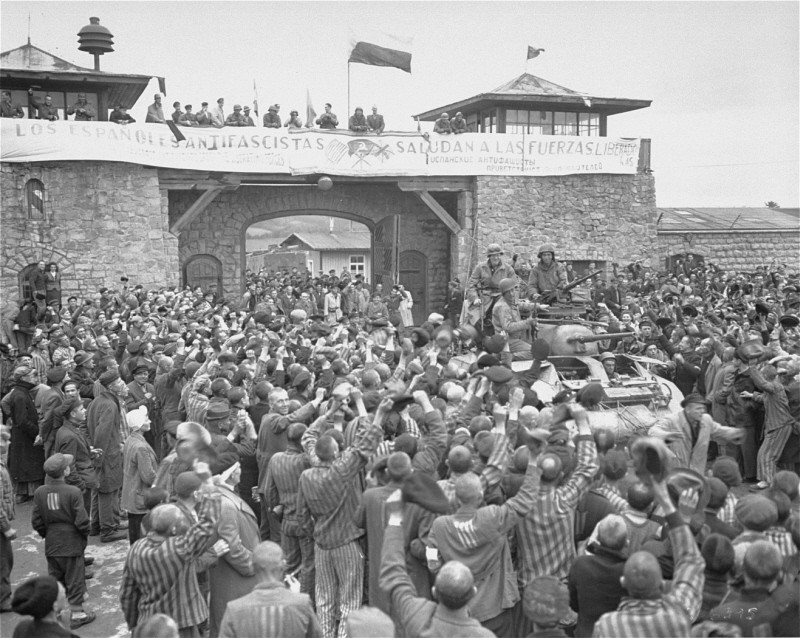

The End of the Holocaust

In the final months of the war, SS guards moved camp inmates by train or on forced marches, often called “death marches,” in an attempt to prevent the Allied liberation of large numbers of prisoners. As Allied forces moved across Europe in a series of offensives against Germany, they began to encounter and liberate concentration camp prisoners, as well as prisoners en route by forced march from one camp to another. The marches continued until May 7, 1945, the day the German armed forces surrendered unconditionally to the Allies.

On May 7, 1945, German armed forces surrendered unconditionally to the Allies. World War II officially ended in most parts of Europe on the next day, May 8 (V-E Day). Because of the time difference, Soviet forces announced their “Victory Day” on May 9, 1945.

In the aftermath of the Holocaust, an estimated 250,000 Jewish survivors found shelter in displaced persons camps run by the Allied powers and the United Nations Refugee and Rehabilitation Administration in Germany, Austria, and Italy. Between 1948 and 1951, most Jewish displaced persons immigrated to Israel, the United States, and other nations outside Europe. The last camp for Jewish displaced persons closed in 1957.

“As time goes on and memories of the Holocaust fade, it is important to remember the barbarity human beings are capable of. It is equally important to contemplate the strength of the survivors and their ability to continue and rebuild their lives. It is our hope that this work of art will promote an appreciation of our shared humanity and a reminder that hatred and intolerance continue to this day and the consequences of the ultimate dehumanization of human beings.”

-Steve Pestka, son of Henry Pestka, a survivor of the Holocaust